Matrixism was a “third-millennium religious movement” (Maćkowiak 2016) based on The Matrix trilogy of films by Larry and Andy Wachowski (Cusack 2010, 3).

These recent groups are generally categorized as new religious movements, although other titles like “hyper-real religions,” “fiction-based religions,” and “invented religions” have been used as candidates to classify them.

Maxtrixism was founded in 2004 as a fully digital internet religion inspired by the stories and universe of The Matrix, the popular, thought-provoking science-fiction film series that first released in 1999 and was followed up by sequels, The Matrix Reloaded (2003) and The Matrix Revolutions (2003). The Matrix franchise also appeared across various other media, including animated films, comic books, and video games.

The Matrix franchise grew in popularity and appeal, leading many scholars over the years to evaluate its content critically. They discovered themes derived from the philosophies of Plato (Hulpoi 2012), René Descartes (Falzon 2006), Arthur Schopenhauer (Segala 2006), Martin Heidegger (Dreyfus 2003), and Jean Baudrillard (Constable 2006, 2009) in the films (Irwin 2002, 2005; Grau 2005; Diocaretz and Herbrechter 2006).

Pathists

Members of Matrixism were active consumers of popular culture who considered the values depicted in cinematic science fiction as more “real” and providing a more meaningful basis for life than many existing “real life” religions.

The original website (www.geocities.com/matrixism) allowed its members called Pathists (also sometimes self-described as Futurists, Matrixists, or Redpills) to register their email addresses as a means of declaring themselves followers of this spirituality (Morehead 2012, 113).

By 2008, there were 2,000 members, although the registration form for the website was later closed in order to emphasize the religion’s decentralized spirituality. Some later websites reported 16,000 members of Matrixism, but no information was given to show or explain how this figure was arrived at (Morehead 2012, 114).

The movement no longer exists today, and the original website was shut down in 2008. Other internet representations of the movement (www.newmatrixism.com, http://www.matrixism.org) also disappeared.

A Summary of the Story of the Matrix

To understand some of the fundamental tenets of Matrixism and Pathist beliefs, one needs to acknowledge the general outline of the narrative of the series.

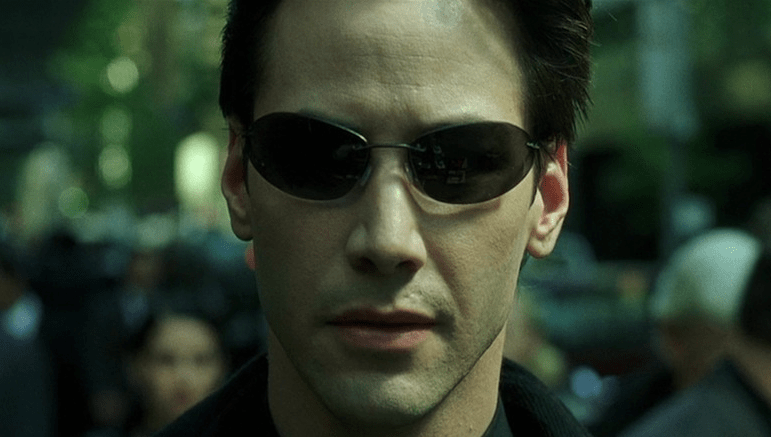

The Matrix trilogy tells of Thomas Anderson, a young computer programmer by day and computer hacker by night who goes under the alias “Neo.”

Neo seeks after Morpheus, a mysterious figure and computer hacker considered a terrorist by state authorities. Neo encounters Trinity, another hacker, who leads him to a meeting with Morpheus, the latter of whom offers Neo an opportunity to find out the answers to his questions and existential angst.

Morpheus gives Neo a choice of two pills. The red pill will reveal the Matrix and the true nature of reality, whereas the blue will allow him to return to his life unchanged. Neo selects the red pill and discovers that his “life” was an illusion in the form of a simulated reality or dream world created by a race of machines.

In reality, the actual world, or “the desert of the real,” which is given the date of approximately 2199 CE, has been devastated by war between humans and machines. This world is divided into three parts: fields of human beings, Zion (the last remaining human city located below the surface of the earth), and the Machine City, a place where Neo goes in the third part of the trilogy in order to fulfill the prophecy, which requires saving the world and humanity. Humans are grown in farms and plugged neurologically into the simulated reality of the Matrix as a means of control so that they can provide an energy source from their bodies for the machines.

Morpheus believes Neo is “The One,” a prophesied figure with the potential to destroy the Matrix and liberate humanity. Reluctantly, Neo comes to accept that he is this figure. Morpheus trains him but can only take him so far, so Neo’s identity as the messianic One evolves over time as he completes his own rite of passage and discovers the path for himself.

As the story reaches its climax, Neo learns to control, manipulate, and reshape the Matrix according to his will and leads the battle against the machines in order to save humanity.

The Matrix as Religious Source Material

Even this most basic outline of the narrative shows that The Matrix entertains deeply religious themes and concepts (Maćkowiak 2016, 86), hence the discovery of many elements characteristic of Buddhism, Christianity, Gnosticism, Islam, and Judaism in it (Ford 2000; Flannery-Dailey and Wagner 2001). The inclusion of diverse religious and philosophical concepts was deliberate; in the words of Larry Wachowski,

[M]ythology, theology and, to a certain extent, higher-level mathematics. All are ways human beings try to answer bigger questions, as well as The Big Question. If you’re going to do epic stories, you should concern yourself with those issues. People might not understand all the allusions in the movie, but they understand the important ideas. We wanted to make people think, engage their minds a bit (Ford 2000, 11).

Popular science fiction media have served to encourage modern-day myth-making. Myths, according to some scholars, are connected to “primal spiritual experiences” (Morehead 2012, 116) and are therefore significant to the “thought patterns and behavior in our postmodern, hi-tech world [which is] deeply symbolic” (Hexham and Poewe 1997, 73). The Matrix is no exception and offers resources germane for religious innovation, imagination, and myth-making.

Myths of science, technology, and human psychology in popular science fiction media are popular resources that are often appropriated by new religious movements. For Pathists, science fiction presented a credible form of new ideas related to ways of seeing and recognizing the “multilayered nature of reality.”

That Matrixism spread over the internet demonstrated the perennial need and imaginative longings people in the contemporary West have for stories speaking to their yearning for meaning (Morehead 2012, 115).

Individualism and Worldview Inclusivity

Matrixism allowed Pathists a significant degree of individualism, encouraging self-reliance “similar to the Protestant Reformation in its innovation that people should read and interpret the Bible for themselves instead of relying on priests to do it for them” (“FAQ,” http://www.geocities.com/matrixism, cited by Maćkowiak 2016, 88).

The “path of the One does not have an exclusivity clause as part of its canon” (“FAQ,” http://www.geocities.com/matrixism, cited by Maćkowiak 2016, 88), meaning that Pathists were encouraged to follow another religious path at the same time. This approach linked the religion’s teachings with other well-established belief systems and worldviews, hence emphasizing unity and harmony between different religious traditions.

Although the movement emerged in 2004, it claimed a longer history going back to 1911 with a connection to the Baha’i religion founded by Baha’u’llah (1817–1892) (Morehead 2012, 113). According to Baha’is, Baha’u’llah is the last of several Messengers from God, which included Abraham, Moses, Buddha, Krishna, Zoroaster, Jesus Christ, and Muhammad. Pathists identify Abdu’l Baha (1844–1921), the son of Baha’u’llah, as a prophetic voice for his making references to “the matrix” in various speeches that were later published in book form.

Several texts that Pathists were encouraged to read beyond the Wachowskis’ trilogy included Aldous Huxley’s (1894-1963) books, The Chronicles of Narnia by C. S. Lewis (1898-1963), Bhagavad Gita, the Bible, Qur’an, and a book about lacrosse, among others (Maćkowiak 2016, 88). As the original website stated, Matrixism was created by “the Wachowski brothers for the most part but also Aldous Huxley, C. S. Lewis and Abdul Baha,” all of whom stood on “the shoulders of giants like “the Buddha and Jesus Christ” (“FAQ,” http://www.geocities.com/matrixism, cited by Maćkowiak 2016, 88).

This rich reservoir of resources from various religious and philosophical traditions offered “sacred content that can be used by audience members for play and serious reflection,” even as religious phenomena that “can compete with the Bible and other religious texts in the imaginative and practical lives” of individuals (Laderman 2009). These resources coalesced to birth a new expression of spirituality in the form of Matrixism (Morehead 2012, 112).

Illusion

Drawing on the motif of illusion, Pathists interpreted the concept of a “computer simulation” as a metaphor of the rules and values of present-day consumer society: “Matrixism looks at the »computer simulation« aspect of The Matrix as a metaphor for the rules, norms and values of our current society. This metaphor also refers to hyper-reality (i.e. television, radio, internet, etc.) which effects people in much the same way as raw (i.e. real) experience” (“FAQ,” http://www.geocities.com/matrixism, cited by Maćkowiak 2016, 89).

The theme of illusion finds parallel with the idea of maya in Buddhist thought (Brannigan 2002), although the concept also appears in Hinduism and Jainism. Maya refers to the illusory nature of human perception of the world. Although “the concrete world does exist… our views and perception of this reality do not match the reality itself. The image in the mirror is not the reality that is in front of the mirror” (Brannigan 2002, 103).

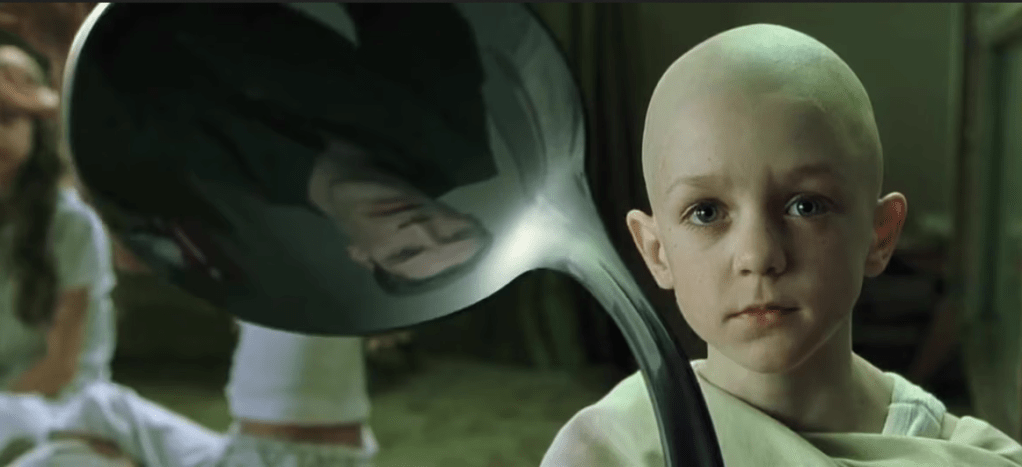

Mirror reflections appear often in The Matrix, no doubt a deliberate inclusion by the Wachowskis intended to teach the viewer “to be careful not to place too much importance on the images that are reflected” (Brannigan 2002, 103). In both Buddhism and The Matrix trilogy, mirrors symbolize “the mental act of reflection, examination, [and] thinking through” (Brannigan 2002, 104).

Arguably the clearest Buddhist reference in The Matrix occurs in the Oracle’s flat, where Neo meets a bold boy adorning a monk’s robe (Maćkowiak 2016, 90). While the boy is bending a spoon with the power of his mind, the viewer can observe Neo’s mirror reflection on the utensil. The boy tells Neo that “There is no spoon… Then you’ll see, that it is not the spoon that bends, it is only yourself,” a riddling utterance like the koans of Zen Buddhism (Cusack 2010, 130).

Another good way to understand the Pathist’s concept of illusion is to consider the ancient Greek philosopher Plato’s allegory of the cave.

In The Republic, Plato presents the scenario of several captives being held chained to a wall in a cave. They have their backs to the cave’s mouth, and just behind them is a fire. Every time an object meets the fire, it casts shadows onto the cave wall in front of them. The captives name these shadows that they perceive to be reality.

When some of the captives exit the cave, they perceive reality anew with the help of the sun and then realize reality as they first perceived it from the shadows was not really reality at all.

One of the lessons of the analogy is that human beings are bound by a limited perception of reality from which they cannot break free. If people could break free, they would experience another realm of reality that would be incomprehensible and beyond their understanding. This realm is what Plato believes is the pure Form of reality that human beings perceive but as an imperfect copy.

In The Matrix, Neo has to gradually adjust to the real world, and after he is released from the Matrix, he complains, “Why do my eyes hurt?” Morpheus responds, “You’ve never used them before.” In Plato’s cave, the captive who is freed is constantly bombarded by the light from both the fire and the light of the sun outside the cave, which causes the captive to go temporarily blind. As Plato stated, “when he came into the light, the brilliance would fill his eyes and he would not be able to see even one of the things now called real? . . . He would have to get used to it.”

Neoplatonism

The Architect and the Oracle are described as supernatural beings and the designers of the world of the Matrix (Maćkowiak 2016, 91).

The Architect manifests the Source, which is the ultimate origin of the programs, the Matrix, the machines, Neo, and the others. The Source corresponds with the Neoplatonic concept of the One (which is also Neo’s epithet) or Universal Intellect, believed to be the principle of reality and the beginning of the chain of emanation. Plotinus, generally regarded as the founder of Neoplatonism, is most well-remembered for his concept of the One, or the Good, inspired by the Republic where Plato presented the Idea of the Good.

Plotinus speculated that through emanation the One gave rise to the Logos or Divine Mind (“Nous”) believed to contain all the Forms and thoughts of a universal intellect. The Architect in The Matrix is likely a representation of Plotinus’ Nous, the demiurge who created the cosmos and in whose mind the forms reside (Brady 2012). The Architect created six versions of the Matrix, the first of which was perfect and, at the same time, a failure.

The Oracle is the mother of the Matrix and represents choice, abnormality, and possibility. Although there appears to be a conflict between the creators, they complement each other: “the Oracle works (through Neo) to save the very world the Architect built” (Hamid 2005, 143).

A Coming Savior

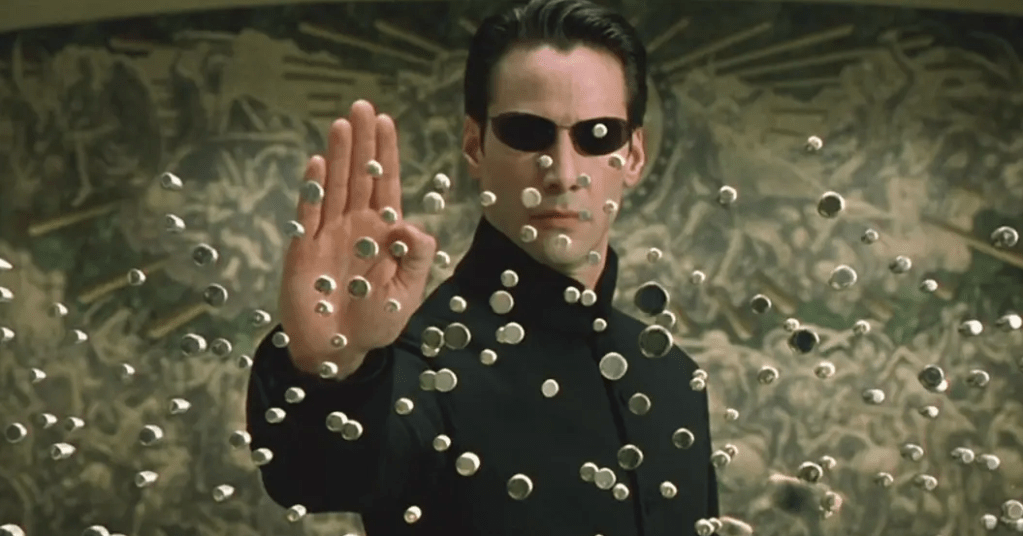

Pathists believed in the prophecy of The One, a messianic figure like The Matrix’s Neo who was prophesied in works of fiction and the world’s religions. The Pathists were given the freedom to adhere to the principles of one or more of the world’s religions until such time as the One returns (Morehead 2012, 114).

The the expectation of the coming One bears clear parallels to the Christian messianic narrative of Jesus Christ who, in Christian belief, was sent by God for the purpose of attaining the salvation of sinful human beings.

Various scenes are similar to biblical episodes involving Jesus as the Messiah. Morpheus not only has faith in the coming “One” but, like John the Baptist does for Jesus, prepares the way for him. In a scene, Morpheus baptizes Neo in the liquid bowels of the human battery chambers, reminiscent of John’s baptism of Jesus in the Jordan. Like Jesus, Neo willingly dies for others, as happens when he is killed by the antagonist Agent Smith while trying to save Morpheus. Also like Jesus, Neo returns to life and later ascends into the sky.

Rituals, Holy Days, and Symbols

Pathists participated in rituals and observed holy days.

There was ritualistic use of psychedelics, viewed by Pathists as an appropriate means for accessing various aspects of the “multi-layered nature of reality” (Morehead 2012, 114). Computer hacking also functioned as a ritual, as through this creative practice the Pathist experienced hyper-reality.

Matrixism had two holy days: 19 April (Bicycle Day) and November 22 (Day of Remembrance and Reflection). Bicycle Day commemorated Albert Hoffman’s experimental use of psychedelics. The Day of Remembrance and Reflection was the anniversary of the day of the deaths of Aldous Huxley, C. S. Lewis, and John F. Kennedy.

With regards to sacred symbols, Matrixism used the Japanese kanji symbol for “red,” which is a reference to the red pill in the film.

References

Brady. 2012. The Matrix and Plato, part 2: Neoplatonism and salvation. Available.

Brannigan, Michael. 2002. “There Is No Spoon: A Buddhist Mirror.” In The Matrix and Philosophy: Welcome to the Desert of the Real, edited by William Irwin, 101-110. Chicago and LaSalle, Illinois: Open Court Publishing.

Constable, Catherine. 2006. “Baudrillard reloaded: interrelating philosophy and film via The Matrix Trilogy.” Screen 47(2):233–249.

Constable, Catherine. 2009. Adapting philosophy: Jean Baudrillard and The Matrix Trilogy. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press.

Cusack, Carole. 2010. Invented Religions: Imagination, Fiction and Faith. Burlington, USA: Ashgate Publishing Company.

Diocaretz, Myriam Díaz., and Herbrechter, Stefan. 2006. The Matrix in Theory. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

Dreyfus, Hubert. 2003. “Existential Phenomenology and the Brave New World of The Matrix.” The Harvard Review of Philosophy 11(1):1-31.

Falzon, Chris. 2006. “Philosophy and the Matrix.” In The Matrix in Theory, edited by Myriam Díaz Diocaretz and Stefan Herbrechter, 95–111. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

Flannery-Dailey, Frances., and Wagner, Rachel. 2001. “Wake up! Gnosticism and Buddhism in The Matrix.” Journal of Religion & Film 5(2):1-32.

Ford, James. 2000. “Buddhism, Christianity, and The Matrix: The Dialectic of Myth-Making in Contemporary Cinema.” The Journal of Religion and Film 4(2):1-16.

Grau, Christopher. 2005. Philosophers Explore The Matrix. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Hamid, Idris Samawi. 2005. “Cosmological Journey of Neo: An Islamic Matrix.” In More Matrix and Philosophy: Revolutions and Reloaded Decoded, edited by Wiliam Irwin, 136-153. Chicago and LaSalle, Illinois: Open Court Publishing.

Hellholm, David. 1983. Apocalypticism in the Mediterranean World and the Near East: Proceedings of the International Colloquium on Apocalypticism, Uppsala, August 12-17, 1979. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck.

Hexham, Irving., and Poewe, Karla. 1997. New Religions as Global Cultures: Making the Human Sacred. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Hulpoi, Claudia. 2012. “Another Apocalypse to Enjoy: The Matrix through Plato’s and Descartes’ Looking Glass.” Ekphrasis. Images, Cinema, Theory, Media.

Irwin, William. 2002. The Matrix and Philosophy: Welcome to the Desert of the Real. Chicago and LaSalle, Illinois: Open Court Publishing.

Irwin, William. 2005. More Matrix and Philosophy: Revolutions and Reloaded Decoded. Chicago and LaSalle, Illinois: Open Court Publishing.

Laderman, Gary. 2009. Sacred and Profane: From Bono to the Jedi Police—Who Needs God?” Religion Dispatches. Available.

Maćkowiak, Anna. 2016. “Mythical Universes of Third-Millennium Religious Movements: The Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster and Matrixism.” MASK 29:85-97.

Morehead, John W. 2012. ““A World Without Rules and Controls, Without Borders or Boundaries”: Matrixism, New Mythologies, and Symbolic Pilgrimages.” In Handbook of Hyper-Real Religions, edited by Adam Possamai, 111-128. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

Partridge, John. 2005. “Plato’s Cave and the Matrix.” In Philosophers Explore the Matrix, edited by Christopher Grau, 239-257. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Segala, Marco. 2006. “The World as Will and the Matrix as Representation: Schopenhauer, Physiology, and The Matrix.” Schopenhauer Jahrbuch 87:185-199.