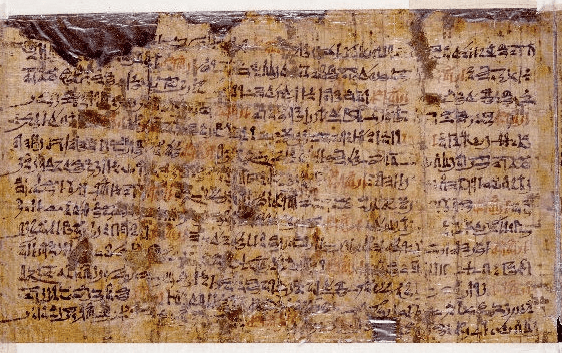

Currently housed in the Dutch National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, Netherlands, the Ipuwer Papyrus is a single, fragmentary papyrus from the Middle Kingdom, the golden age of Egyptian writing (c. 1980–1630 BCE). This text—also called The Admonitions of an Egyptian Sage—is named after an ancient Egyptian sage and overseer of singers, Ipuwer.

See: The Biblical Exodus: The Story (Part 1)

See: The Biblical Exodus: Historicity, Maximalism vs. Minimalism, and Doubts (Part 3).

_____________________________________________________________________________________

This second entry in this series on the biblical exodus outlines several features of the Ipuwer Papyrus and criticizes Christian apologia for erroneously using it as an independent source attesting to some of the biblical plagues occurring just before the Hebrew exodus recorded in the book of Exodus in the Old Testament.

Composition and Date of the Ipuwer Manuscript

The manuscript contains Ipuwer’s speech to the Pharaoh and the royal court and is divided into seventeen columns and would originally have contained at least 236 lines of text, roughly 660 verses. The manuscript has been dated to the late Twelfth Dynasty (lasted BCE c. 1939-1760) or the Thirteenth Dynasty (lasted BCE c. 1759-1630) (Parkinson 2002, 50; Enmarch 2008, 4–25; Stauder 2013, 509). The poem preserved on it itself dates earlier into the Middle Kingdom (BCE c. 2080-1760) (Parkinson 1991, 60).

The Content of the Ipuwer Manuscript

The text, which Ipuwer delivered to the “Majesty of the Sovereign,” is referred to as a lamentation (15.13). Ipuwer laments how chaos has swept through Egypt, resulting in catastrophe and the need for restoration. According to Egyptologist Roland Enmarch (2009), a leading commentator on the Ipuwer Papyrus,

“The poem provides one of the most searching explorations of human motivation and divine justice to survive from ancient Egypt, and its stark pessimism questions many of the core ideologies that underpinned the Egyptian state and monarchy. It begins with a series of laments portraying an Egypt overwhelmed by chaos and destruction, and develops into an examination of why these disasters should happen, and who bears responsibility for them: the gods, the king, or humanity.”

Ipuwer emphasizes that because of the people’s disregard for order, there emerges a state of national hardship and chaos: “Forsooth, (men’s) hearts are violent. The plague is throughout the land. Blood is everywhere. Death is not lacking. The mummycloth speaks, before one draws near it” (2.5–6). Famine, desecration, epidemics, death, natural disasters, theft, violence, social revolution, and more are the consequences of this disorder.

Powerful images and metaphors are used throughout the lamentation: “Squalor” permeates the land, and none have “white clothes” (2.8); only groaning is found throughout the land, mingled with lamentations (3.13–14); both the “great and small [say]: ‘I wish I might die.’” (4.2–3); the young are hungry as “there is no food” (4.14–5.2); the “children of princes are dashed against walls” (4.3), the king’s palace is stripped bare (3.9), and “noble ladies suffer like slave-girls” (4.11–12); even the hearts of the animals “weep.” (5.5) and the birds are hungry as “no fruit nor herbs can be found for them” (6.1). The roads traveled are perilous as they “are guarded. Men sit over the bushes until the benighted (traveller) comes, in order to plunder his load. What is upon him is taken away. He is belaboured with blows of the stick, and slain wrongfully” (5.11–12).

Ipuwer presents “a world upturned” (Enmarch 2008). There is a societal revolution, and the rich are becoming poor and the poor are becoming rich: “The poor of the land have become rich, and (the possessor) of property has become one who has nothing.” (8.2) “He who never slept upon walls is (now) the possessor of a bed.” (7.10) and “the wealthy are in mourning. The poor man is full of joy” (2.7-8); “the robber is a possessor of riches [and the rich man is become] a plunderer” (2.8-9); and noble ladies go hungry (9.1). According to Ipuwer, “the land has been deprived of the kingship (7.2), meaning that the Egyptians are not only fighting invaders but also among themselves. The only remedy is a central government that preserves peace and harmony.

Enmarch continues, explaining that Ipuwer presents a “schematic antiideal “inverted world” (verkehrte Welt) that elaborates the topos of order versus chaos. The setting of Ipuwer is vague, with no clear references to specific historical events, emphasizing the lament descriptions’ timeless relevance” (2008, 39).

Independent Evidence for the Plagues of Exodus?

According to some Christian apologists, the Ipuwer Papyrus provides an independent, extrabiblical witness to some of the exodus events and plagues described in the Old Testament book of Exodus. The apologist’s contention, which is based on a commitment to a stringent literalism hermeneutic, emphasizes the objective historicity of the biblical account of the plague events that occurred shortly before the Hebrews left Egypt under Moses’ leadership.

As Enmarch rightly observes, “The broadest modern reception of Ipuwer amongst non-Egyptological readers has probably been as a result of the use of the poem as evidence supporting the Biblical account of the Exodus” (2011, 173-174). However, such is not the view and consensus of Egyptologists. Several reasons support this view, such as the following.

Chronologically Out of Date

On the assumption that the biblical exodus by which Moses guided the Hebrews out of Egypt was a historical event, it has been dated earliest in the 1400s BCE, although scholarly consensus places it in the thirteenth century BCE. Regardless of one’s perspective, even if one accepts the Ipuwer Papyrus‘s chronologically earliest date of composition, 1630 BCE, the last year of the Thirteenth Dynasty, the biblical exodus is centuries apart from the events described in it. The cited events described in the book of Exodus and the Ipuwer Papyrus cannot be the same.

An Invasion, Not a Mass Emigration

The Ipuwer Papyrus conflicts with the biblical account; for instance, instead of reporting a migrating population fleeing Egypt, it chronicles an invasion (Gardiner 2011, 6). It refers to unwelcome foreign people who have become firmly rooted in the land: “the desert is throughout the land. The nomes are laid waste. A foreign tribe has come to Egypt. The Delta is overrun by Asiatics” (3.1). According to Enmarch, this “contradict[s] the Biblical account… imply[ing] that they described different occasions. For example, the Egyptian poem actually laments the invasion of Asiatics rather than their largescale emigration” (2011, 173).

The biblical exodus, on the other hand, describes a large migrating population fleeing Egypt for a Promised Land, described as “a good and spacious land, a land flowing with milk and honey” (Exodus 3:8). Later on in this series, we will examine hypotheses regarding the size of this alleged migrating population.

Ahistorical

The Ipuwer Papyrus is not a historical account (Enmarch 2008, 19-20; Enmarch 2011, 174). The schematic literary nature of some of the poem’s laments contain “no preserved historical setting, no kings’ names, very few and generalised toponyms and ethnonyms” (Enmarch 2011, 174). The work is essentially ahistorical (Parkinson 2002, 207) and represents a theodic “reproach to god” by which Ipuwer admonishes the Lord of All for Egypt’s descent into chaos (Morris 2020, 231).

Furthermore, even when there appear to be historical references to specific events, like rebellion against the Pharaoh and despoiling royal tombs, they lack specificity and refer to “activities [that] are likely to have happened numerous times in Egyptian history” (Enmarch 2011, 174). The “setting of Ipuwer is vague, with no clear references to specific historical events, emphasizing the lament descriptions’ timeless relevance” (Enmarch 2008, 39). Ipuwer’s account is both hyperbolic and vague (Morris 2020, 234) and that “the contradictions that express chaos… signal the fictional nature of the text…” (Parkinson 2002, 207).

The River Turning Red

The Ipuwer Papyrus contains superficial similarities with the biblical account, by offering a brief mention of flooding and a detail about a man “who walks upon the road until he sees the flood” (13.2–5). Most cited by apologists is the description of the water’s transformation into bloody redness or blood: “Forsooth, the river is blood and (yet) men drink of it” (2.10). Similarly, in the book of Exodus, Moses “raised his staff in the presence of Pharaoh and his officials and struck the water of the Nile, and all the water was changed into blood” (7:20-21).

A few considerations should give one pause that these are necessarily historical descriptions of the exact same event. For instance, it is important to acknowledge the available physical explanations for the Nile’s floodwaters taking on a reddish color that may lie behind descriptions in ancient sources of it transforming into blood. There is evidence that the massive reproduction of red algae bloom—a harmful plant-like organism that survives in the sea and freshwater—due to favorable conditions has provided large bodies of water with a reddish color called a “red tide” (Howard 2023; National Ocean Service 2024). Possibly, this common natural phenomenon could be the source of inspiration for ancient metaphorical descriptions of waters taking on a red color, which is likened to blood.

Probably more likely in terms of a physical explanation is red soil (Kitchen 2003, 250; Enmarch 2011). According to Enmarch, “this detail [in the Ipuwer Papyrus] is a metaphorical description of what happens at the times of catastrophic Nile floods when the river is given the appearance of blood due to carrying large quantities of red soil” (2011, 174). Heavy rains resulted in “extra[-]high flood(s)” that “would have brought a suitably large and intense amount of very red earth (Roterde)” along with them (Kitchen 2003, 250).

The Ipuwer Papyrus and the biblical description in Exodus would both then refer to the same kind of natural phenomenon (Kitchen 2003, 252-254). Enmarch remarks that because such inundations probably occurred on numerous occasions over Egypt’s history, “it would not however be possible, on this basis alone, to identify the two texts as describing the same actual event” (Enmarch 2011, 175).

On the other hand, other interpretations of the waters becoming blood are possible that do not require a physical explanation. For example, as a metaphor, evoking pervasive violence where life-giving water has undergone the most dire change imaginable (Enmarch 2011, 175). Parallels are present in other ancient literature like the Aeneid and Apocalypse of Asclepius, suggesting this imagery is widespread and that it may be inappropriate to posit a specific link between two particular occurrences of it (Enmarch 2008, 28).

Enmarch concludes that based on “these reasons, attempts to link the poem to a historical event that might also be recorded in Exodus are unconvincing” (2011, 174).

Other Similarities

Other similarities not infrequently cited by some apologists are too characteristic of destruction in general to be demonstrative parallels between the Ipuwer Papyrus and the biblical plagues in Exodus.

Some of these include the presence of fire and the destruction of agricultural fields and trees in both accounts (Ipuwer P. 7.1; Exodus 9:23-24; 10:15); the suffering and/or death of animals and cattle (Ipuwer P. 5.5; Exodus 9:1–3); the presence of dead humans (Ipuwer P. 2.6–7), including among the young (Ipuwer P. 4.3–4; Exodus 12:29-30); and cries or mourning in the land (Ipuwer P. 1.6; Exodus 12:30). These details can describe countless events entailing the destruction of human life and settlements through history and across civilizations, whether through violence or natural disaster.

One can assert similarly regarding the Ipuwer Papyrus’s references to rebels and servants abandoning their subordinate status (e.g., 6.7–8; 10.2–3). The likes of pillaging tombs and graves, the destruction of lucrative structures and symbols of power (e.g., palaces), and social uprising are equally too characteristic of historical insurrections and revolutions generally to be demonstrative of independent attestation between the Ipuwer Papyrus and the biblical plagues recorded in Exodus.

See Part 3: Dating the Biblical Exodus and Doubts Regarding its Historicity (forthcoming)

References

Enmarch, Roland. 2008. A World Upturned: Commentary on and Analysis of “The Dialogue of Ipuwer and the Lord of All.” London, England: The British Academy.

Enmarch, Roland. 2011. “The Reception of a Middle Egyptian Poem: The Dialogue of Ipuwer and the Lord of All in the Ramesside Period and Beyond.” In Ramesside Studies in Honour of K. A. Kitchen, edited by Mark Collier and Steven R. Snape, 169-175. Bolton, England: Rutherford Press Bolton.

Gardiner, Alan Henderson. 2011. Admonitions of an Egyptian Sage from a Hieratic Papyrus in Leiden. United States: Nabu Press.

Howard, Jenny. 2023. “What exactly is a red tide—and how does it affect humans?” National Geographic. Available.

Kitchen, Kenneth A. 2003. On the Reliability of the Old Testament. Grand Rapids, Michigan, United States: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Morris, Ellen. 2020. “Writing Trauma: Ipuwer and the Curation of Cultural Memory.” In An Excellent Fortress for His Armies, a Refuge for the People: Egyptological, Archaeological, and Biblical Studies in Honor of James K. Hoffmeier, edited by R. E. Averbeck and K. L. Younger, Jr., 231-252. University Park, Pennsylvania, United States: Penn State University Press.

National Ocean Service. 2024. “What is a red tide?” National Ocean Service. Available.

Parkinson, R. B. 2002. Poetry and Culture in Middle Kingdom Egypt: A Dark Side to Perfection. New York, United States: Continuum.

Stauder, Andréas. 2013. Linguistic Dating of Middle Egyptian Literary Texts (Lingua Aegyptia Studia Monographica 12). Hamburg, Germany: Widmaier.

[…] See: A Response to Christian Apologetic Uses of the Ipuwer Papyrus (Part 2)__________________________________________________________________________ […]

There are other proofs of the Hebrews being in Egypt in the 1876-1446 BC time frame.

A papyrus of the 1809–1743 BC era gives Hebrew names of slaves. Even more interesting is the names of Asiatic slaves. Peoples were much more traveled and intermingled in that era then we realized.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Papyrus_Brooklyn_35.1446#

https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/3369

An 1378-1348 BC inscription at the temple of Soleb references the Israelites wandering in the wilderness.

https://archive.org/details/egyptcanaanisrae00redf/page/n15/mode/2up page 272/3

https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/6596/

[…] regarding the historicity of the biblical exodus as it is described in the biblical sources.See: A Response to Christian Apologetic Uses of the Ipuwer Papyrus (Part 2)See: A Critique of the “Early Date” for the Biblical Exodus (Part 4) […]