There is a “material turn” in the academic study of religion in which, among several interests, symbolism is stressed (Hazard 2013).

See Analyzing Religion Through Video Games: Bandit Religion and Kincaid’s Shrine (Borderlands 2) (Part 2)

See Part 4 (forthcoming)

____________________________________________________

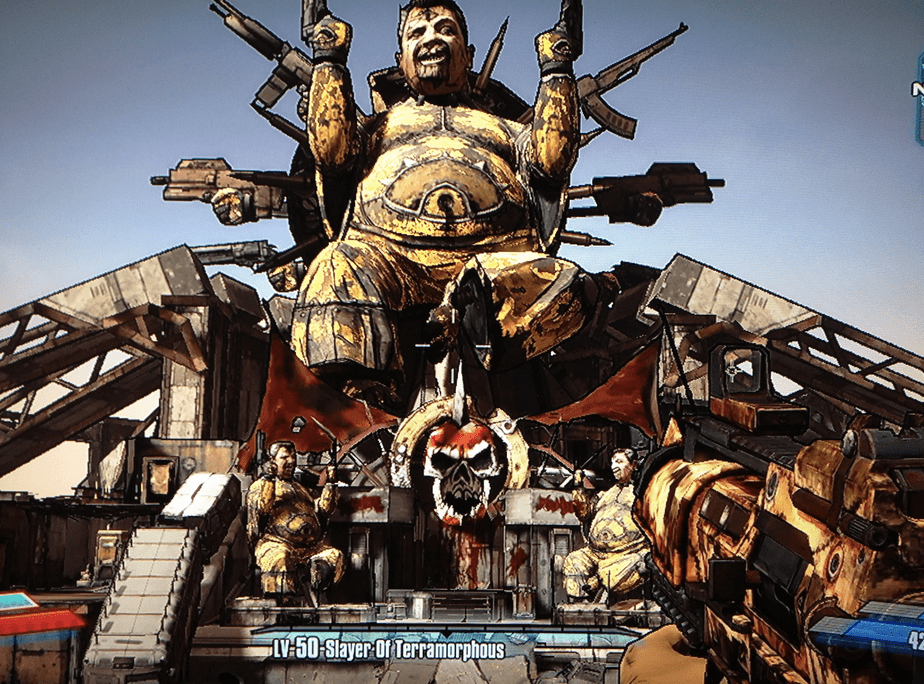

In accordance with this interest, as the previous entry showed, the material objects constituting the Shrine of the Gunslinger—a sacrificial altar erected by the Bloodshot bandits of Borderlands 2 in veneration of Marcus Kincaid, a morally corrupt arms merchant who exploits Pandora’s warring factions for personal wealth and gain—are important symbols requiring analysis for understanding Bloodshot religion based on what it communicates to observers, whether to the unfortunate sacrificial victim being led to the altar for incineration or the bandits who collectively convene before it.

The analysis demonstrated that these symbols (a large central skull, an assortment of weaponry both shown in the statue’s hands and protruding out the sides of its back in a circular shape, the imposing size of the structure, its caterpillar tank wheels, blood smears and stains, human skeletal remains, etc.) coalesce to reveal a fanatical, militant religion whose blood-obsessed devotees partake in warfare and sacrifice.

This participation in warfare entails an ideology of zealous commitment to a divinized Kincaid, of survival, a willingness to sacrifice the body for causes, which include the procurement of food supplies and discarded munition resources, scavenging for materials and equipment purposeful to maintaining settlements, terrorizing and slaughtering outsiders for sport and/or sacrifice, and defending their mostly small, unwalled outposts against environmental threats across Pandora.

Color Symbolism in Religions

Having already discussed the symbolism of some of the major material elements of the Bloodshot religion, we can turn to the use and role of color.

Although an analysis of colors might seem trivial, scholarship has long realized that they maintain symbolic significance across cultures and religions (Griffiths 1972; Couacaud 2016). Color may shape an individual’s experience of the world and how society gives particular spaces, objects, and moments meaning (Biggam et al. 2022).

Based on Bloodshot religion and identity, at least two important colors require analysis: red and gold. I discuss the color gold and its symbolic value in real-world religions and cultures in the next entry in this series and therefore limit myself exclusively to red.

Red is arguably one if not the most used colors in real-world religions for symbolic purposes (other popular colors include yellow, blue, white, and black), possibly because of possessing a semblance to the sun, especially at sunset (Yu 2014, 58), fire and light, and the life-blood or life-principle that determines, sustains, or nurtures existence (Chevalier and Gheerbrant 1996, 792).

But utilizing color to represent and embody meaning would be impossible if one could not reason or think symbolically. The historical record shows that this ability was present in humans almost 100,000 years ago. A 92,000-year-old ochre record from Qafzeh Cave, a prehistoric archaeological site located in modern-day Israel, showed the human capacity for symbolic behavior since the ochre was deliberately selected and mined specifically for its color (Hovers, Ilani, Yosef, and Vandermeersch 2003).

Red ochre was important for the Neanderthals based on its use in their burials as early as 60,000 years ago (Roebroeks et al. 2012). These burials likely offer evidence of early notions of life after death (Mircea and Couliano 1991) and may indicate a ceremonial process to ensure safe passage to the next world (Smart 1998, 37).

Red held significance for the ancient Egyptians (Roebroeks et al. 2012), and although often representing life and living, it represented death in the Celtic world (Yu 2014, 50). Red is one of the primary symbolic colors in Chinese thought to represent the world and boons (associated with good fortune, happiness, and celebration, often projected through using red lanterns during festivals), Mayan architecture and aesthetics (e.g., the Etemenanki Ziggurat in Babylon was painted in different colors corresponding to the planets, with red ascribed to Mars), for magical purposes (e.g., Australian Aboriginal warriors painted red on their spears), as ceremonial or religious attire (e.g., Roman Catholic cardinals wear red to symbolize their willingness to die for their faith).

For ancient Egyptians, red represented the desert and the destructive god Seth, who had red hair and eyes, and, for the ancient Jews, sin (e.g., “Though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be as white as snow; though they be red like crimson, they shall be as wool” [Isaiah 1:18]). For Christians, red symbolizes the blood of Jesus Christ shed on the cross for the sins of humankind and for martyred saints. The color appears on torri gates through which one moves when entering Shinto temples and shrines, with these gates representing the entering into a sacred place. Red was also the sacred, vitalizing color of ancient China’s Chou Dynasty (c. 1050–256 BCE).

What is true of real-world religions is also true for the fictional Bloodshot bandit religion of Borderlands 2. Red finds obvious appeal for the bandits, no doubt because of a macabre association with blood, hence underscoring and underpinning a fanatical ideology of warfare and sacrifice.

Bloodshot symbolism of red appears as the antithesis of the color’s association with life. Whereas the Neanderthals sprinkled the bodies of their deceased with red pigment as a way of restoring to them the “warm” color of blood and life (Yu 2014, 58), the Bloodshot bandits spew their walls with graffiti and iconography of what appears to be made of the blood of their victims. Both fresh and dry blood stain the sacrificial altar of Kincaid’s shrine and the open space in front of it. In addition, the group’s primary identity marker is a logo of a red (bloodshot) eye, which itself requires commentary.

Seeing Red: Eye Symbolism in Bloodshot and Real-World Religions

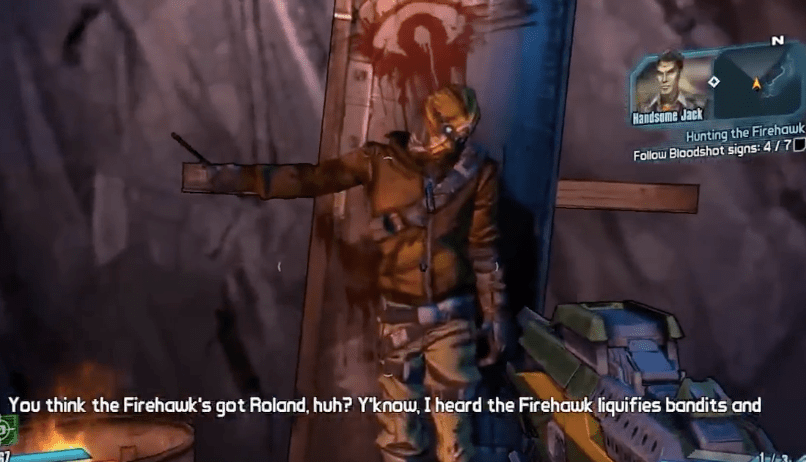

This logo adorns the cracked concrete walls of the Bloodshot stronghold’s labyrinth tunnels and is etched into the tattooed bodies of the bandits themselves. Wherever the eye symbol is visible, an obvious link is made to the Bloodshot bandit gang who controls a particular territory, such as the frozen wastes and, in the case of its stronghold and base of operations, the Dahl 3rd Brigade Memorial Dam.

The Bloodshots’ eye is artistically rendered in a noticeably more rectangular than strictly ovular form, which gives it sharpness, whereas a more circular rendition would be much easier on the perceiver’s eye (pun intended) and not entirely consistent with Bloodshot ideology and iconography that emphasizes roughness, sadism, and violence.

Much of the Bloodshot aesthetic stresses sharpness: knives and blades of various forms and kinds are carried around by them everywhere; edges of many objects have been deliberately sharpened, like the spikes atop the makeshift iron sheet walls surrounding the premises of the Shrine of the Gunbringer and the bullets protruding in a circular shape from behind Kincaid’s statue, giving them a blade-like aesthetic; and razor-sharp objects adorning the equipment of Bloodshot units, such as the Crazed Marauder’s spikes. In some cases, the number of spikes protruding from bandit gear differentiates them. The Killer Marauder is a stronger version of a regular bandit Marauder and is distinguishable by the spikes above his mask. One should add that even the Bloodshot masks have bright red lenses for an eye socket aesthetic, which establishes overall consistency with the religion’s color theme and identity, although one must wonder how practical and useful such a lens color is for the one brandishing them.

Retuning to the Bloodshots’ eye logo, its iris, pupil, and cornea contain different shades of red. The central pupil is a bright red surrounded by the darker red hue of the iris, which is then surrounded by the cornea containing the same bright red as the pupil.

Medically, a bloodshot eye is a result of subconjunctival hemorrhage, which occurs after a blood vessel underneath the clear surface of the eye breaks. The surface cannot absorb blood quickly, leading to the blood being trapped and causing the white part of the eye to turn bright red.

Although the eye symbol demarcates Bloodshot territory and identity, symbolically, it is not immediately clear what it represents for this group, especially in light of the diversity that this symbol boasts in real-world religions and cultures. Eyes can represent good or evil, divine or devilish elements, protection or destruction, among many other concepts and themes.

The symbol appears in ancient Mesopotamian literature (Seawright 1988), sculptures, iconography, sacred objects, amulets, and prayers (Dilek 2021). In ancient Egyptian mythology, the Eye of Horus was a sign of prosperity and protection, derived from the myth of Isis and Osiris and portrayed on amulets. The Eye of Ra was glorified during temple rituals to protect the pharaoh, sacred places, and ordinary people, hence why it was depicted on boats to ensure safe sea voyages (Freeman and Ray 1997, 91).

The Divine Eye is a symbol for the Highest God in Caodaism, an indigenous religion that emerged in the southern region of Vietnam in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Bao 2024). For Sufis, the “eye” is narrated as the “eye of the heart,” which for the mystic is essential for “meeting God” in this world and the hereafter (Jafari and Jafari 2019).

In material depictions of Shiva, the third god of the Hindu Trinity (Trimurti), who is both the Preserver and Destroyer of the universe, this deity has a third eye located in the center of his forehead (Dhillon, Singh, and Dua 2009). The third eye contains various meanings. It represents the power of knowledge, energy, fire, and protection against evil. When Parvati blindfolded Shiva while he meditated, the universe plunged into chaos. To save creation, Shiva formed a third eye from which fire emerged to recreate light and order and annihilate evil. Many Hindus wear a tilak between the eyebrows to represent the third eye, which represents enlightenment.

The Evil Eye

According to this widespread belief, receiving a glance from someone who possesses this supernatural power can cause the recipient great misfortune (fever, illness, a headache, the destruction of property, etc.) or even death. Could the Bloodshot logo of a bloodshot eye be connected to this evil eye concept?

Belief in the evil eye appeared in many cultures across the ancient world, especially among the Babylonians, Chinese, Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans, as well as in various indigenous cultures. According to Mesopotamian mythology, the sky god An created demons that represented the principal source of the evil eye because of their malicious intent behind diseases, famines, disasters, and other calamities they caused to befall human lives and livelihoods. In ancient Irish mythology, Balor, king of the giants, had a large poisonous eye that killed whatever it looked at, and the snake-haired Medusa, queen of the Gorgons in Greek mythology, had the power to kill those who beheld her grotesque face by turning them into stone.

Belief in the evil eye is held by many today in the United States (Heimlich 2009), Africa (Finneran 2003; Nyambura, Nyamache, and Gechik 2013), the Middle East (Abu-Rabia 2005), Islamic or Islamic-majority countries (Saida 2021; Falak Naz and Aslam 2023), as well as in Western (Pew Research Center 2018), Central (Pócs 2004), and Eastern European countries (Pew Research Center 2018).

Who may be suspected of wielding this sinister power since anyone could potentially have it? (Lykiardopoulos 1981, 223-224) Among the English, anyone who sits and peers passionately and long into a fire may be suspected. Across Mediterranean locations, where people genetically have darker eyes, a person with blue eyes is imagined to possess the evil eye. On the other hand, among the Northern Irish, it is those with darker eye colors. In many instances, outsiders or foreigners have been suspected. The Cretans and Cypriots, who perhaps traveled widely and therefore often strangers, had a reputation for being particularly endowed with the evil eye. In these instances, being different physically or socially from average members in close communities, renders one susceptible to being suspected of having this power.

Several factors were believed to make certain people particularly susceptible to being or becoming a victim of the possessor of the evil eye. People who were happy and/or wealthy and powerful were greatly envied, which made them targets. Infants and children were also believed to be significantly harmed by the evil eye, a belief possibly reinforced by high infant mortality rates enhanced by poor hygiene and medical care.

So fear-inducing is this ominous power that cultures derived various means of protection against it. Protection required wearing or carrying material objects and/or a behavior of some kind, such as spitting, praying, gesturing, or walking in a certain manner (Lykiardopoulos 1981, 225). Children in Hungary wear a red ribbon, and, among twentieth-century Greeks, spitting on a child’s face was a means of safeguarding the child from becoming a victim of the evil eye. Amulets of objects representing the defensive parts of animals, like horns, teeth, and claws were worn by adults.

Beads, salt, and plants like shamrock (in Ireland) and garlic (in Greece) are used as defensive measures. In Scotland, chamber- pots filled with salt were given as marriage gifts, with a portion of it being sprinkled over the floor to protect against the evil eye (Rorie 1934). Marriage is a source of great happiness for those being wedded, which may render them vulnerable to the envy of others and therefore increase the chances of them being cursed.

According to kabbalistic theology, the power of the evil eye can be offset by the color blue, a belief derived from a medieval kabbalistic myth about the blue garment of the feminine aspect of the godhead (Sagiv 2017). Among ancient Greeks, the mask of Medusa was used to avert the evil eye.

For the Bloodshot bandits, one must wonder if the concept of the evil eye has relevance to their many glaring eye logos graffitied across walls, tattooed into their flesh, and carved into the circular golden relics found in their stronghold. Perhaps the eye is not intended only to convey omniscience (see below) but also to strike fear into the hearts of outsiders or intruders in their territories who believe they will be cursed for falling into its gaze. These parallels do, however, remains speculation.

The All-Seeing Eye

Most likely, in my view, is that the Bloodshot logo symbolizes an all-seeing vision underscoring a sense of omnipresence and omniscience.

My religions and mythologies portray omniscient and/or omnipresent beings. Zeus, the supreme Olympian deity of the ancient Greeks, was characterized as the all-seeing eye, and the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara is believed by Tibetan Buddhists to be all-seeing. In Buddhist mythology, Avalokiteshvara is represented with multiple heads whose “thousand pairs of eyes” look into every direction (Gordon 1952, 44). Yahweh, the supreme deity of the ancient Jews, is all-seeing, for he “observes everyone on earth; his eyes examine them” (Psalm 11:4), and his “eyes… are on those who fear him, on those whose hope is in his unfailing love” (Psalm 33:13-15, 18). In Proverbs, “The eyes of the Lord are everywhere, keeping watch on the wicked and the good” (15:3).

This concept of the all-seeing eye carries over into the New Testament. In the Epistle to the Hebrews: “Nothing in all creation is hidden from God’s sight. Everything is uncovered and laid bare before the eyes of him…” (4:13) and in a letter ascribed to the apostle Peter, “For the eyes of the Lord are on the righteous and his ears are attentive to their prayer…” (1 Peter 3:12).

The symbol eventually became embedded in the architectural and iconographic traditions of Christianity (Zavalii 2022, 190). By the end of the fifteenth century, the eye symbol, enclosed in a triangle, appeared on church architecture, icons, and paintings as an image symbolizing the omnipresence of God and the Holy Trinity.

In a church in Cyprus called the Virgin Panagia (“All-Holy”), Jesus Christ is artistically rendered on the dome, intentionally drawing the viewer’s attention to his all-seeing gaze that follows those occupying the sacred space, no matter where one stands (Binning 2017). The symbolism is deliberate and meaningful, since Christ’s all-seeing gaze is intended to provoke the conscience of the congregants, therefore leading them to confession and requests for forgiveness from the sin that Christ self-sacrificially shed his blood on the cross for.

In terms of the Bloodshot religion of Borderlands 2, it is not clear if these bandits ascribe omniscience to Kincaid or if there exists a link between Kincaid and the eye symbol. What is certain, however, is that the symbol is central to Bloodshot identity and communicates its control over particular territories, such as its major stronghold at the Dahl 3rd Brigade Memorial Dam. It forcefully conveys to outsiders, who are immediately perceived as threats needing to be eliminated and bearers of loot to be plundered, that they are in a location ruled by the ruthless Bloodshots.

In this sense, somewhat similar to the all-seeing eye in various religious traditions, the eye symbol indicates omniscience and therefore a warning to others that the Bloodshots (and/or Kincaid) perceive everything that happens in their territory.

Conclusion

Focusing on elements of macabre Bloodshot religiosity in Borderlands 2 allowed an opportunity to observe the symbolic importance the “eye” has in many real-world religions and cultures. Since video games and other popular entertainment media are cultural products reflecting the real-world cultures in which they are produced, it is unsurprisingly that many familiar cultural elements of religion also permeate the planet of Pandora in Borderlands 2.

A brief discussion of real-world cultural and religious mythologies regarding the eye shows that it features diversely: as a source of evil, curses, or death and destruction; the omnipresent vision of a being; as an icon of a god; in prayers, hymns, and sacred literature; enlightenment; an engraving or carving in an amulet for protection; or as an architectural piece in aesthetically impressive churches or cathedrals, in which they have been depicted on statues, in paintings, or engraved on stone facades and slabs.

What is true of real-world religions is also true for the fictional Bloodshot bandit religion. The red, bloodshot eye so vividly featured in the bandits’ logo symbolizes an omnipresent vision intended to warn outsiders or intruders that they have entered a hostile territory controlled by the zealous and fanatical Bloodshots, who will show them little mercy, if any at all. These outsiders are given the unsettling feeling of perpetually being observed by the sinister and omnipresent glare of the bloodied eye.

Color symbolism was discussed. Red was the color primarily observed for its obvious symbolic popularity and aesthetic appeal in real-world religions and presence in scriptures, mythologies, and icons. Since this color featured prominently in Neanderthal burials, it is possibly the earliest/most ancient color humans used symbolically for sacred reasons that we have on record. Like the eye, red came to boast diverse symbolism: life, fire, the sun, blood, sacrifice, celestial objects, gods, magic, and features in religious attire and on sacred objects like the gate leading into Shinto shrines.

Red is also the most obvious and thematic color of choice for Bloodshot identity, featuring in the blood stains of victims staining many surfaces in its locations and on the sacrificial altar to Kincaid, tattoos adorning their bodies, the primary logo, the seemingly unhinged slogans sprawled on walls in blood, draping and well-worn red fabric cloths and canvases scattered about the Bloodshot stronghold, and on gear (e.g., red eye lenses of Bloodshot masks and blood splattering the mask’s surface).

Red finds obvious appeal for the Bloodshots because of its macabre association with blood, hence underscoring an ideology of warfare and sacrifice, both of which appear to be frequent rituals practiced by this group.

References

Abu-Rabia, Aref. 2005. “The Evil Eye and Cultural Beliefs among the Bedouin Tribes of the Negev, Middle East.” Folklore 116(3):241-254.

Bao, Nguyen Thai. 2024. “The Symbol of the Divine Eye in Caodaism.” IJSSHMR 3(7):884-888.

Binning, Ravinder S. 2017. “Christ’s all-seeing eye in the dome.” In Aural Architecture in Byzantium: Music, Acoustics, and Ritual, edited by Bissera Pentcheva, 101-126. New York and London: Routledge.

Biggam, Carole P., Wolf, Kirsten., Steinvall, Anders., and Street, Sarah. 2022. A Cultural History of Color in the Modern Age. London, United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Chevalier, Jean., and Gheerbrant, Alain. 1996. A Dictionary of Symbols. London, United Kingdom: Penguin Books.

Couacaud, Leo. 2016. “Does Holiness Have a Color? The Religious, Ethnic, and Political Semiotics of Colors in Mauritius.” Signs and Society 4(2):176-214.

Dhillon, Neeru., Singh, Arun D., and Dua, Harminder S. 2009. “Lord Shiva’s Third Eye.” British Journal of Ophthalmology 93(2).

Dilek, Yeşim. 2021. “Eye Symbolism and Dualism in the Ancient Near East: Mesopotamia, Egypt and Israel.” Turkish Journal of History 74:1-30.

Eliade, Mircea, and Couliano, Ioan. 1991. Handbuch der Religionen. Düsseldorf, Germany: Artemis & Winkle.

Falak Naz, Nida., and Aslam, Naeem. 2023. “Development and Validation of Belief in Evil Eye Scale.” Pakistan Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 21(2):18-27.

Finneran, Niall. 2003. “Ethiopian evil eye belief and the magical symbolism of iron working.” Folklore 114(3):427-432

Freeman, Charles., and Ray, J. D. 1997. The Legacy of Ancient Egypt (FACTS ON FILE’S LEGACIES OF THE ANCIENT WORLD). New York, United States: Checkmark Books.

Gordon, Antoinette K. 1952. Tibetan Religious Art. New York, United States: Columbia University Press.

Griffiths, J. Gwyn. 1972. “The Symbolism of Red in Egyptian Religion.” In Ex orbe religionum, edited by Class J. Bleeker, 81-90. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill.

Hazard, Sonia. 2013. “The Material Turn in the Study of Religion.” Religion and Society: Advances in Research 4:58–78.

Heimlich, Russell. 2009. Eyed by Evil. Available.

Hovers, Erella., Ilani, Shimon., Yosef, Ofer Bar., and Vandermeersch, Bernard. 2003. “An Early Case of Color Symbolism Ochre Use by Modern Humans in Qafzeh Cave.” Current Anthropology 44(4):491-522.

Jafari, Samaneh., and Jafari, Tayyebe. 2019. “A comparative study of the Eye of the Heart in Islamic Sufism and the Third Eye in Yoga.” Journal of Literary Arts 12(2):83-92.

Lykiardopoulos, Amica. 1981. “The Evil Eye: Towards an Exhaustive Study.” Folklore 92(2):221-230.

Nyambura, Ruth., Nyamache, Tom., Gechik, Bernard. 2013. “Evil Eye: An African Overview.” Journal of Education and Social Sciences 2(1):114-121.

Pew Research Center. 2018. Eastern and Western Europeans Differ on Importance of Religion, Views of Minorities, and Key Social Issues. Available.

Pócs. É. 2004. “Evil Eye in Hungary: Belief, Ritual, Incantation.” In Charms and Charming in Europe, edited by J. Roper, 205-228. London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan.

Roebroeks, Wil., Sier, Mark J., Nielsen, Trine Kellberg., Loecker, Dimitri De., Maria Parés, Josep., Arps, Charles E. S., and Mücher, Herman J. 2012. “Use of red ochre by early Neandertals.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109(6):1889-1894.

Rorie, David. 1934. “Chamber Pots Filled with Salt as Marriage Gifts.” Folklore 45(2):162–163.

Sagiv, Gadi. 2017. “Dazzling Blue: Color Symbolism, Kabbalistic Myth, and the Evil Eye in Judaism.” Numen 64(2-3):183-208.

Saida, Tobbi. 2021. “Manifestation Of Evil Eye Belief In Algerian Efl Learners’ Compliment-Responding Strategies.” ASJP 13(6):38-46.

Seawright, Helen L. 1988. “The symbolism of the eye in Mesopotamia and Israel.” Masters dissertation, Wilfrid Laurier University.

Smart, Ninian. 1998. The World’s Religions. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Teschler-Nicola, Maria., et al. “Ancient DNA reveals monozygotic newborn twins from the Upper Palaeolithic.” Communications Biology 3(650):1-11.

Yu, Hui-Chih. 2014. “A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Symbolic Meanings of Color.” Chang Gung Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 7(1):49-74.

Zavalii, Oleksandr. 2022. “Research of the Symbolic and Allegorical Composition of the “Eye of Providence” in the Cultural Heritage of the Trypillia Protocivilization and Religious Analysis Context.” Humanities and Social Sciences 10(3):190-196.

[…] In an area called Bloodshot Ramparts in Borderlands 2 (2012), The Shrine of the Gunbringer was erected by local Bloodshot bandits in honor of Marcus Kincaid, whom they call the “The Gunbringer.” Kincaid is an ideologue of unrestrained capitalism in the form of a profit-driven arms dealer on Pandora who occupies an important ludological role of selling ammunition and weapons to players, as well as partaking in some narrative elements.See Part 1: Analyzing Religion in Borderlands: Intro, Overview, and Method See Part 3: Analyzing Religion Through Video Games: Bloodshot Eyes and Color Symbols in Religions (Borderlands 2…___________________________________________ […]