The study of religion in video games, a subset in both media and video game studies generally, is a young discipline that continues to develop and have a positive future (Pötzsch and Jørgensen 2023).

History of Video Games and Video Game Studies

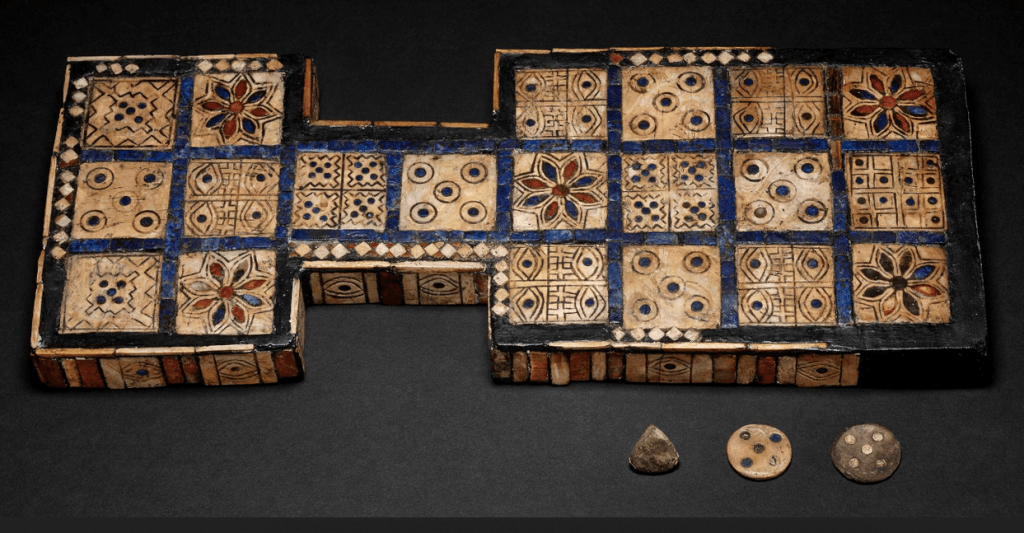

Gaming generally has always been part and parcel of human culture, with some of the earliest on historical record being the Royal Game of Ur dating to 2,400 BCE and Senet from Ancient Egypt around 2,600 BCE. Nabatean board games have been uncovered in Petra and the Chinese game Go began thousands of years ago and is still played with enthusiasm in Japan and Korea.

The earliest digital interactive games are a little more recent, dating in the 1950s, and perhaps initially created for academic purposes (Stahlke and Mirza-Babaei 2022, 22–29; Wardyga 2023, 4). Noughts and Crosses (OXO) was birthed by Alexander Douglas, a PhD student at Cambridge University in 1952, and just a few years later William Higinbotham’s Tennis for Two (1958) followed, which was played on an oscilloscope. In 1962, a group of programmers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology developed Spacewar!, and exactly ten years later Pong (Atari Corporations 1972) came onto the scene. Other impressive digital interactive games emerged during this early period through Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney. Much of the academic research into video games followed two decades later (Wolf 2008).

Early controversies emerged, such as concerns about the affect violent video game content may have on players (Fernández-Vara 2019, 8-9). Death Race, released in 1976, glorified violence by having players plough over pedestrians, then marking a tombstone on the spot where these pedestrians were mercilessly slaughtered.

The Death Race controversy was possibly the earliest of what would become episodic media and public sensationalism over violent material in video games, which continued into the twenty-first century (Jenson and de Castel 2021).

Especially popular franchises like Grand Theft Auto (Rockstar Games 1997-) (Pichlmair 2008) and first-person shooter war series’ such as Call of Duty (Activision 2003-) and Battlefield (various developers 2002-) (Suziedelyte 2021, 112) all offer players an array of virtual behaviors, activities, and choices within their structure and design, many of which are obviously violent, have been singled out for shaping player attitudes by nurturing in them aggressive attitudes, which putatively caused or contributed to deviants’ decisions to perform extreme acts of violence (e.g., school shootings) (Foster 2016).

During this early period, arcade games became popular and very accessible in public spaces like shopping malls or restaurants. In the United States, the period between 1980 and 1985 has been labeled “the Golden Age of video arcades” (Compton 2000, 58-59).

Yet, despite the golden age of arcade gaming machines, technological advancements made in the 1980s produced strong competition in the form of home computers and home consoles. Modems enabled connectivity via phone lines, allowing home computers to dial up to bulletin board systems (BBSs) and multiuser domains (MUDs), which made early networked games and online games for multiple players possible (Wolf 2021, 427). Home computers were the primary means of playing massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs) in the latter half of the 1990s and into the 2000s. This became possible on console too with the release of SEGA’s Dreamcast in 1998 in Japan and 1999 in North America.

During the 1980s, some began expressing their ideas about video games, leading to occasional theorizing, such as Chris Crawford’s The Art of Computer Game Design (1982). These years and the 1990s were accompanied by academic interest in video games from a psychological perspective, especially on aggression and socialization (Wolf and Konzack 2021, 2180).

The 1990s witnessed the decline of arcade games. Home consoles and home computers became the main competitors in the video game industry (Wolf 2021, 427) while, in research circles, there also emerged the ludology–versus–narratology debate (Bosman 2019, 30, 103; cf. Bosman 2016, 30-33). This became the first major point of scholarly disagreement in the field of video game studies over how to best approach video games as a researcher: as things to be exclusively or primarily played (ludus) (e.g., Juul 2001), or primarily as narratives that are told to the player through interaction between player and game (e.g., Hansen 2010).

According to game designer and academic Gonzalo Frasca, “Although at its core it remains a valid discussion, the debate itself has lost steam in the academic world and is now seen as one of the foundational discussions of modern game studies” (2021, 1182). The two perspectives are now considered by many researchers to be complementary rather than conflicting or irreconcilable (Wolf and Konzack 2021, 2181).

Such earlier disagreements did not deter scholarly interests in the early twenty-first century (Raessens 2006). It became undeniable that the video game industry is lucrative, a fact giving it obvious sociological and anthropological significance. As one scholar observes, this field of study will continue “growing as a relevant field of social research as long as gaming is a huge, widespread, transnational, transcultural, and mass social phenomenon which deserves as much attention as more “classical” fields of study” (Testa 2014, 251).

This field of study continued to grow. The organizers of the first international academic journal of computer game research, Game Studies, identified 2001 “as the Year One of Computer Game Studies as an emerging, viable, international, academic field” (Aarseth 2001). Academic journals became dedicated to the study of video games, notably Game Studies (2001), Games and Culture (2006), and Eludamos (2007). Methodological frameworks for analyzing video games were conceptualized (Konzack 2002; Aarseth 2003).

The Digital Games Research Association (DiGRA) conference emerged in 2003, appearing first in Utrecht, the Netherlands, followed by conferences in Vancouver, Canada (2005), Tokyo, Japan (2007), and then in Brunel, West London (2009). A series of local DiGRA conferences were established in the likes of DiGRA Australia, DiGRA Nordic, and Chinese DiGRA conferences (Mäyrä 2021, 536-537).

In December 2007, the University of Potsdam became the first German university institution to study computer games on an interdisciplinary basis after media philosopher Dieter Mersch founded The Digital Games Research Center (DIGAREC) (Günzel, Liebe, and Möring 2021, 533). Its work focused on several features of video games, including the structural, aesthetic, technical, and performative aspects. The center continues to host international lectures, workshops, and conferences on the topics of ludic boredom, serious games, in-game photography, and gamification.

Having now moved into the 2020s, video game studies has become one of the “fastest-growing branches of media studies” (Wolf and Konzack 2021, 2180).

The Study of Religion in Video Games

Researchers of religion wished not to be left out of the vibrant discussions on the nature of video games.

Many researchers acknowledged the lack of critical analysis of religion in video games and the need for more scholarly attention (Campbell and Grieve 2014; Vallikat 2014, 9), and presented apologia for why scholars interested in religion or theology should take video games seriously (Detweiler 2010; Corliss 2011; Campbell and Grieve 2014; Vallikat 2014; Campbell et al. 2015; Bosman 2019).

Although there existed some early efforts to integrate religion with video game design (e.g., Richard Garriott’s Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar [1985]), the intersections between digital games and religion remained understudied. Even as recently as 2014, Gregory Grieve and Heidi Campbell stated that “the study of religion and gaming not received much attention in the study of religion and the internet and remains one of the most understudied elements of such digital environments” (2014, 14-15).

This is, in their view, for at least four discernible reasons: “games are widely considered simply a form of young people’s entertainment; video games are often seen as artificial or unvalued forms of expression; technology is thought to be secular; and virtual gaming worlds are seen as unreal” (Grieve and Campbell 2014, 16-17). Each of these misconceptions and others have encountered serious and sustained critique.

In 2007, in a panel entitled Born Digital and Born Again Digital: Religion in Virtual Gaming Worlds, scholars presented their work on religiously themed games, the problematic appearance of violent narratives in religious gaming, and the rise of the Christian gaming industry (Grieve and Campbell 2014, 56). The following year, the panel Just Gaming? Virtual Worlds and Religious Studies discussed the use and presence of religious rituals and narratives in mainstream video gaming.

The need for a more focused study of religion in gaming and virtual worlds led to the release of a slew of landmark publications, notably Halos & Avatars (Craig Detweiler, 2010), Godwired (Rachel Wagner, 2011), eGods (William Sims Bainbridge, 2013), Of Games and God (Kevin Schut, 2013), Playing with Religion in Digital Games (Heidi A. Campbell and Gregory P. Grieve, 2014), and Methods for Studying Video Games and Religion (Vít Šisler, Kerstin Radde-Antweiler, and Xenia Zeiler, 2018).

Journals, such as Gamenvironments (2014-) and Online – Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet (2004–2010 and 2014–present), continue providing substantive critical analyses of religion in video games, while many researchers have made this the central topic for their dissertations (Corliss 2011; Kim 2012; Perreault 2015; Steffen 2017; Tregonning 2018; Bishop 2022–).

References

Aarseth, Espen. 2001. “Computer Game Studies, Year One.” Game Studies. Available.

Aarseth, Espen. 2003. “Playing Research: Methodological approaches to game analysis.” Semantic Scholar. Available.

Bishop, James. 2022-. “The Representation of Religion and its Interpretation by Audiences in Fantasy-Fiction Video Game and Film Media.” PhD dissertation, University of Cape Town.

Bosman, Frank G. 2016. “The Word Has Become Game: Researching Religion in Digital Games.” Online – Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet 11:28-45.

Bosman, Frank G. 2019. Gaming and the Divine: A New Systematic Theology of Video Games. London and New York: Routledge. (Apple Books pagination).

Campbell, Heidi A., and Grieve, Gregory Price. 2014. “Introduction: What Playing with Religion Offers Digital Game Studies.” In Playing with Religion in Digital Games, edited by Heidi A. Campbell and Gregory P. Grieve, 14-56. Indiana, U.S.: Indiana University Press. (Apple Books pagination).

Campbell H. A., Wagner R., Luft, S., Grieve, G. P., and Zeiler, X 2015. “Gaming Religionworlds: Why Religious Studies Should Pay Attention to Religion in Gaming.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 84(3):1–24.

Compton, Shanna. 2000. “Walkthrough: an Introduction.” In Gamers, edited by Shanna Compton. New York, U.S.: Soft Skull.

Corliss, Vander I. 2011. “Gaming with God: A Case for the Study of Religion in Video Games.” Senior dissertation, Trinity College.

Detweiler, Craig. 2010. Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games With God. Louisville, Kentucky, U.S.: Westminster John Knox Press.

Fernández, Clara. 2019. Introduction to Game Analysis (2nd ed.). London and New York: Routledge.

Foster, Heather. 2016. “How do Video Games Normalize Violence? A Qualitative Content Analysis of Popular Video Games.” Masters dissertation, Northern Arizona University.

Frasca, G. 2003. “Ludologists Love Stories, Too: Notes from a Debate That Never Took Place.” Digital Games Research Conference 2003 Proceedings.

Hansen, Chris. 2010. “From Tekken to Kill Bill. The future of narrative storytelling?” In Halos and Avatars: Playing video games with God, edited by Craig Detweiler, 19-33. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press.

Juul, Jesper. 2001. “Games telling stories? A brief note on games and narratives.” Game Studies 1(1). Available.

Kim, Hanna. 2012. “Religion and Computer Games: A Theological Exploration of Religious Themes in World of Warcraft.” PhD dissertation, University of Birmingham.

Perreault, Gregory. 2012. “Holy Sins: Depictions of Violent Religion in Contemporary Console Games.” Paper presented at 2012 Conference on Digital Religion Center for Religion, Media and Culture, Boulder, CO, USA, January 12–15.

Pichlmair, Martin. 2008. “Grand Theft Auto IV Considered as an Atrocity Exhibition.” Eludamos: Journal for Computer Game Culture 2(2):293-296.

Pötzsch, Holger., and Jørgensen, Kristine. 2023. “Futures of Games and Game Studies.” Eludamos: Journal for Computer Game Culture 14(1):1-183.

Raessens, Joost. 2006. “Playful Identities, or the Ludification of Culture.” Games Culture 1(1):52–57.

Stahlke, Samantha., and Mirza-Babaei, Pejman. 2022. The Game Designer’s Playbook: An Introduction to Game Interaction Design. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Stahlke, Samantha., and Mirza-Babaei, Pejman. 2022. The Game Designer’s Playbook: An Introduction to Game Interaction Design. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Steffen, Oliver. 2014. “’God Modes’ and ’God Moods’: What Does a Digital Game Need to Be Spiritually Effective?” In Playing with Religion in Digital Games, edited by Heidi A. Campbell and Gregory P. Grieve, 379-420. Indiana, U.S.: Indiana University Press. (Apple Books pagination).

Suziedelyte, Agne. 2021. “Is it Only a Game? Video Games and Violence.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 188:105–125.

Testa, Alessandro. 2014. “Religion(s) in Videogames: Historical and Anthropological Observations.” Online – Heidelberg Journal for Religions on the Internet 5:249-278.

Tregonning, James. 2018. “God in the Machine: Depicting Religion in Video Games.” Dissertation, University of Otago.

Vallikatt, Jose. 2014. “Virtually Religious: Myth, Ritual and Community in World of Warcraft.” PhD dissertation, RMIT University.

Wardyga, Brian J. 2023. The Video Games Textbook: History • Business • Technology (2nd ed.). London and New York: Routledge.

Wolf, Mark J. P. 2008. “The Study of Video Games.” In The Video Game Explosion: A History from PONG to PlayStation and Beyond, edited by Mark J. P. Wolf, 21-28. London, England: Bloomsbury Academic.

Wolf, Mark J. P. 2021. Computer Games.” In Encyclopedia of Video Games: the Culture, Technology, and Art of Gaming (2nd ed.), edited by Mark J. P. Wolf, 424-429. ABC-CLIO, LLC. (Apple Books pagination).

Wolf, Mark J. P., and Konzack, Lars. 2021. “Video Game Studies.” In Encyclopedia of Video Games: the Culture, Technology, and Art of Gaming (2nd Edition), edited by Mark J. P. Wolf, 2179-2183. ABC-CLIO, LLC. (Apple Books pagination).

A lot of games have this ability