Along with visuals, gameplay, technical polish, and duration, narrative or storytelling is a key component of what makes a video game. The significance and function of story in video games, as well as the mono-myth template used in the popular God of War (Sony Interactive Entertainment 2018), are discussed in this article.

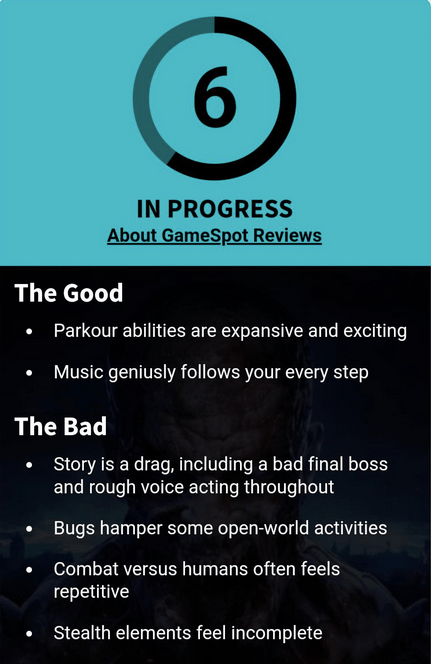

For the majority of video game enthusiasts, including reviewers, players, developers, and publishers, narrative is crucial. As with many review-based websites and game journalists (e.g., IGN, GameSpot, Metacritic, PC Gamer), it is typically taken into consideration when a reviewer assigns a numerical or starred rating to a certain video game (Cassidy 2011, 299-300). A reviewer’s rating will frequently, but not always, be lowered by a story that is poor and/or unclear.

Immersive storytelling is important for the experience of the majority of players. The “appeal for many games resides in their ability to envelop players in new worlds, complete with sophisticated backstories and complex plots” (Newgren 2010, 138). According to research, 95% of interviewees stated that a good story line matters to their experiences as it sets the mood, tone, and overall strategy (Hodge 2010, 164).

Likewise narrative is crucial for developers and project leads. Programmers, animators, visual designers, visual effects artists, sound designers, game testers, and other professionals work together as part of the multidisciplinary field of game design (Mauger 2021, 776-781; Stahlke and Mirza-Babaei 2022, 53, 60-62). Story writers, who are largely in charge of crafting cohesive narratives that breathe life into the fictional universe or planet and its varied cast of people, are crucial team members.

“Storytelling is part of game design. Even games without a “real” story will leave players creating stories out of their own trials, successes, and failures. For those games that do employ a traditional narrative, the characters and world that live within can have a lasting impact on the players that come to know them” (Stahlke and Mirza-Babaei 2022, 238).

Numerous well-known and financially supported video games (such as The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt [CD Projekt 2015] or Far Cry 5 [Ubisoft 2018]) and their developers provide “elaborate storyline[s], including full-fledged non-playable characters with their own background stories, main and side quests” (Bosman 2019, 81).

Functionally, storytelling elements, like quests and mythologies (Hodge 2010, 175), are “device[s] for advancing through the game, the fictional world of setting, characters and myths, and the mechanics of narrative and the game experience” (Vallikat 2014, 19). Actors (such as hunters or vampires), objects (chests or doors), actions (initiating character dialog or killing enemies), states (being damaged or empowered), events (dying to a boss or escaping a wreck), and cinematics or “cutscenes” are examples of common story elements (Gee 2006, 59).

In hindsight, the most brilliant writers and innovative thinkers are drawn together by the need for a compelling narrative. George R. R. Martin, the author of the A Song of Ice and Fire novel series, was hired by FromSoftware, the company that developed Elden Ring (2022). Notably, Martin’s ideas served as the basis for a large portion of the popular high fantasy entertainment series Game of Thrones (2011-2019).

By working together, Martin combined historical fiction, epic poetry, and myth to create the overall mythology for Elden Ring’s world. In this scenario, the player assumes the character of a Tarnished, a member of an exiled group, who returns to The Lands Between, a stunning but dark and perilous world in an attempt to reconstruct the titular Elden Ring. After the immortal Queen Marika smashed the ring, its fragments, known as Great Runes, were acquired by a number of strong and antagonistic demigods. In order to restore the Elden Ring and ascend to the position of Elden Lord, the player must travel across The Lands Between as a Tarnished.

Martin and the developers intended for this story to be both superior to the stories presented in the previous Dark Souls editions and non-intrusive. The plot of Elden Ring is straightforward, mysterious, and, despite never overburdening players, is constantly there in the background. Martin’s contributions were the subject of later debates, with some critics asserting that the finished work lacked Martin’s writing style and distinctive storytelling flavor (Orland 2022; Velocci 2024). In any case, these crucial conversations highlighted how important narrative is for many people when it comes to video games, particularly when prominent figures from the industry are involved. This undoubtedly helps to raise anticipation and enthusiasm.

Elden Ring nonetheless released to critical “universal acclaim,” placed on several major video game of the year (GOTY) listings by established video game companies (PC Gamer, GameSpot, IGN, Polygon, etc.), and winning several of them (e.g., D.I.C.E. Awards, The Game Awards, Game Developers Choice Awards, Golden Joystick Awards, to name a few).

It has been argued that even significantly less complex video games, like Pong (Atari 1972) or Pac-Man (Namco 1980), perhaps considered by some to be trivial “low” forms of commercial electronic entertainment (Mäyrä 2009, 3), can also be narratologically analyzed (Bosman 2019, 81). Tetris (Alexey Pajitnov 1985), which consists of little more than players needing to move pieces or blocks of various shapes and sizes descending into the playable space, is arguably a criticism of contemporary capitalism and capitalist societies (Murray 2017).

Marie-Laure Ryan has also argued that all games, simulated or real-life, abstract or not, possess a narrative dimension (2006, 75–93, as cited by Bosman 2019, 97). Using fictional versions of a live radio broadcasting report of a football match, Ryan argues that it is psychologically almost impossible for a audiences to not interpret the match in some form of narrative, such as, for example, about the virtues or vices of the players or the background story of the top scorer.

Video game cinematics, more commonly called “cutscenes” (O’Grady 2013, 104) are also important storytelling devices that serve to inform the player about her role in relation to the video game’s universe and overarching narrative (Wagner 2014, 108-109).

Cutscenes use television and film production aesthetics and conventions, rendering them a film sequence that includes various camera angles, forward-motion movement, speed acceleration or deaccelaration, slow motion, infinite framing possibilities, orchestral music, among other techniques (Blanchet 2021, 481-482). They can vary in length and will occur between periods of gameplay and during the developing story arch (Vallikat 2014, 20). Cutscenes are mostly, although not always, displayed without the interaction of the player, who becomes a passive spectator. They also often present a shift or progression in the plot line of the story.

The Mono-myth in Video Games

The concept of “mono-myth” is a potent narrative tool. Developers have utilized it in video games (Rollings and Adams 2003, 95–109), and academics who research video game narratives encourage careful examination of it (Cassar 2013).

Because of Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949) and its influence on the film industry, the classic hero who triumphs after a difficult journey has generally had a profound resonance in popular culture and the general public’s psyche.

It is clear that the hero archetype has resonance in many different cultures and dates back to ancient times. This is true of the ancient Babylonians, Hebrews, Hindus, and Egyptians, whose “stories and poetry aimed to glorify their princes and warriors,” as well as the Greeks, particularly in the renowned poet Homer’s The Odyssey (c. 750 BCE) (Krzywinska 2008, 126).

By using the mono-myth of a hero who lives in a normal environment but is called to adventure, video games continue to pass along this ancient tradition to contemporary audiences.

Video games continue to hand down to modern audiences this ancient tradition by incorporating the mono-myth of a hero who exists in an ordinary world in which he is called to adventure. The hero, outlines Campbell, ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won. The hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man (1999, 23).

Continued here.

References

Cassar, Robert. 2013. “God of War: A Narrative Analysis.” Eludamos. Journal for Computer Game Culture 7(1):81-99.

Cassidy, Scott B. 2011. “The Videogame as Narrative.” Quarterly Review of Film and Video 28(4):292-306.

Rollings, Andrew., and Adams, Ernest. 2003. Andrew Rollings and Ernest Adams on Game Design. Indianapolis, Indiana, United States: New Riders.

Dmitrievich, Belousov E., Khuzeeva Liliia R. 2022. “The concept of Hero’s journey in modern video games and its influence on the gamer’s self-identity.” Proceedings of the International University Scientific Forum 8(1):67-74.

Mäyrä, Frans. 2009. “Getting into the Game: Doing Multi-Disciplinary Game Studies.” In The Video Game Theory Reader (2nd ed.), edited by Bernard Perron and Mark J. P. Wolf, 313-329. London and New York: Routledge.

Hodge, Daniel W. 2010. “Role Playing: Toward a Theology for Gamers.” In Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, edited by Craig Detweiler, 163-175. Louisville, Kentucky, United States: Westminster John Knox Press.

Klepek, Patrick. 2017. “‘God of War’ Creative Director Cory Barlog on Nihilism and Fatherhood.” Vice. Available.

Krzywinska, Tanya. 2008. “World Creation and Lore: World of Warcraft as a Rich Text.” In Digital Culture, Play, and Identity: A World of Warcraft Reader, edited by Hilde G. Corneliussen and Jill Walker Rettberg, 123–142. Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States: MIT Press.

MacDonald, Keza. 2018. “God of War’s Kratos was an angry lump of muscle. I made him a struggling father.” The Guardian. Available.

Murray, Janet H. 2017. Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States: MIT Press.

Newgren, Kevin. 2010. “BioShock to the System: Smart Choices in Video Games.” In Halos and Avatars: Playing Video Games with God, edited by Craig Detweiler, 135-148. Louisville, Kentucky, United States: Westminster John Knox Press.

Orland, Kyle. 2022. “Elden Ring review: Come see the softer side of punishing difficulty.” Ars Technica. Available.

Ryan, Marie-Laure Ryan. 2006. Avatars Of Story. Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States: University of Minnesota Press.

Velocci, Carli. 2024. “How much of Elden Ring did George R.R. Martin write?” Polygon. Available.