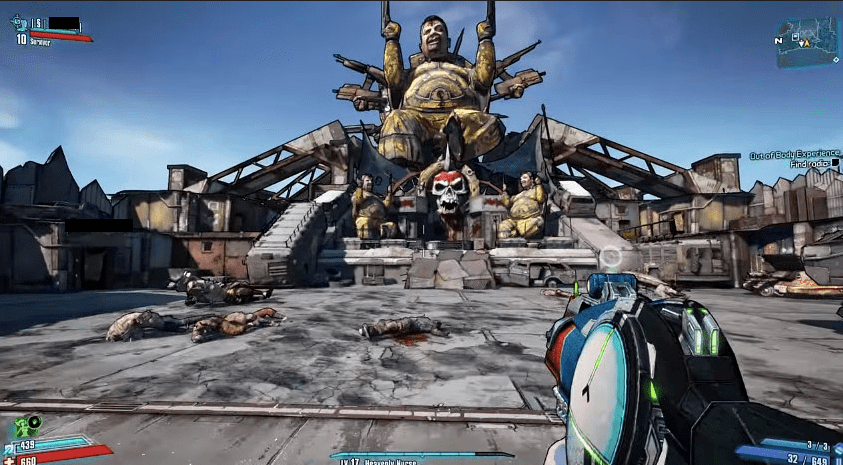

In an area called Bloodshot Ramparts in Borderlands 2 (2012), The Shrine of the Gunbringer was erected by local Bloodshot bandits in honor of Marcus Kincaid, whom they call the “The Gunbringer.” Kincaid is an ideologue of unrestrained capitalism in the form of a profit-driven arms dealer on Pandora who occupies an important ludological role of selling ammunition and weapons to players, as well as partaking in some narrative elements.

See Part 1: Analyzing Religion in Borderlands: Intro, Overview, and Method

See Part 3: Analyzing Religion Through Video Games: Bloodshot Eyes and Color Symbols in Religions (Borderlands 2)

___________________________________________

In addition to players, Kincaid supplies munitions to the bandit factions and settlements scattered across Pandora’s parched surface. In order to build good will with one major bandit faction, the Bloodshots, Kincaid supplied them with a complimentary crate of munitions to secure their future business. This was Kincaid’s effort to profit from the war waging between the Bloodshots and the Crimson Raiders. The latter, another major faction consisting of ex-soldiers and Vault Hunters, are the “good guys,” featuring many of Borderlands’ major protagonists.

Evidently, as the player learns from Echo recordings uncovered through exploring, the sophistication of the munitions Kincaid supplied the Bloodshots with was enough to convince them that he is a god. And what does the history of religion inform one about the veneration of a god or goddess? It is that devotees erect a shrine in its honor and/or offer sacrifices upon an altar. Such is the case for the Bloodshot bandits; in an Echo recording, a bandit, in comedic-intended derangement, exclaims:

Flanksteak! FLANKSTEAK! Can you – can you BELIEVE these guns Marcus gave us?! There’s a shotgun in here that shoots FIRE! [EXPLETIVE] FIRE! I been usin’ it to roast my food and girlfriends – Marcus is a – is a GOD! Me and the boys got an idea – a good idea, you see? Great idea. We build him a shrine. Big shrine. Beautiful shrine. And he’ll keep givin’ us guns. More guns! MORE GUNS! MORE GUUUUNS!”

The Bloodshots offer prayers in the form of chants to Kincaid while also declaring their adoration for him: “Chant louder, boys! Marcus can’t hear us! GUNS! GUNS! GUNS! GUNS! GUNS! WE LOVE YOU, MARCUS THE GUNBRINGER! WE LOVE YOUUUU!”

This profit-driven episode of Kincaid supplying a crate of free munitions to the bandit faction, motivating them to venerate him as a god and commit acts of extreme violence, attests to their unhinged character. This is a deliberate choice on behalf of the developers to give Borderlands a general comedic effect, even though the material used for its frequent social, political, and religious commentary can be of a serious nature (e.g., genocide, colonialism, greed, and, if one is a Bloodshot, setting girlfriends aflame). The Bloodshots believe that propitiating Kincaid, as one would a god, can produce rewards in the form of guns and ammunition.

In addition, what does the material aesthetic of the statue of Kincaid reveal about Bloodshot religiosity? Immediately apparent is an ideological obsession with bloodlust, barbarity, and armaments.

First, the size of the statue gives it a sense of grandeur, power, and status. In a violent world, physical size and the weaponry one carries matter greatly.

A large skull with a steel spike adorns Kincaid’s feet. Six weapons, two of which are pistols held in the hands directed skyward, are displayed. A large set of caterpillar wheels is planted firmly on the righthand side of the statue, undoubtedly ascribing it an imposing tank-like aesthetic. Two miniature versions of the large statue, displayed at slight angles and also holding pistols in each hand, are placed on opposing sides of the altar facing and drawing attention to the sacrificial pit.

The walls behind and alongside the sacrificial pit contain fresh bloodstains, indicating recent ritual activities involving the sacrificial killing of some creature, human or other. Based on the type of skeletal remains in the pit, it is safe to assert that sacrificing humans to their god, Kincaid, is a core Bloodshot ritual.

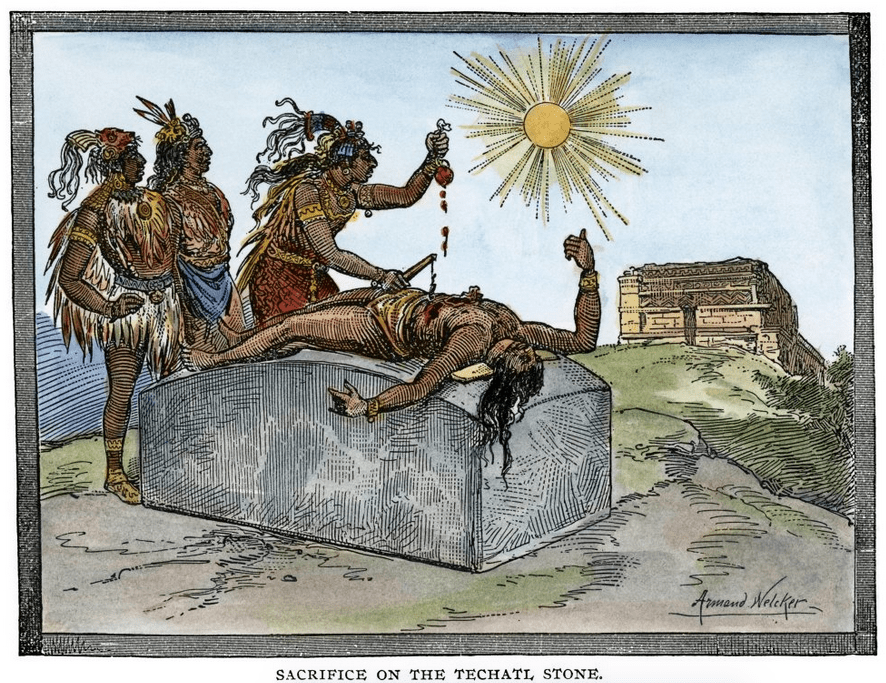

Borderlands 2‘s gamified rendition of Bloodshot religion perhaps reminds one of the macabre religious rituals of the Aztecs, a Mesoamerican people whose civilization lasted from 1300 to 1521, reputable among scholars for their practice of human sacrifice (Anawalt 1982; Graulich 2000; Pennock 2012).

The Aztec process was a little more gruesome than a speedy incineration of a victim in the steel tubular pit below Kincaid’s feet. The sacrificial victims of the Aztec priests, often a prisoner of war, had their still-beating hearts cut out and then offered to the gods in a vessel called a Cuauhxicalli (“eagle gourd bowl”). The victim’s body was then rolled down the stairs to a stone terrace at the base. The head was removed, as were sometimes the arms and legs, and skulls were displayed on a rack.

Not all Aztec sacrifices required cutting the heart out of live humans. Offerings to the gods also took the form of self-inflicted bloodletting (“autosacrifice”). Nobles, for example, felt that being able to shed their own blood for the gods was in fact an honor. The process included the use of obsidian knives, stingray spines, and the sharp spines of the maguey plant to penetrate the skin, which could be drawn from the shin, knee, elbow, tongue, ear, or foreskin.

As noted, glancing into the sacrificial pit below Kincaid’s statue reveals the unremoved remains of the bones and skulls of previous incinerated victims, also indicating, in addition to the massive skull fixed above the pit, that human bones are valuable artifacts in the Bloodshot religion and may even be connected to an ideology of warfare.

The ideological backing for the Aztecs’ ritual was their conviction that blood and human sacrifice appeased the gods and persuaded them to not bring an end to the present age, that of the fifth sun. The sun god, Huitzilopochtli, was engaged in an ongoing battle with darkness, and he needed strength through blood in order for the sun to continue in its cycle.

The Bloodshots of Borderlands and most, although not all bandits (e.g., Martyrs), similarly intend to ensure their survival, despite their overt brainlessness, especially in Pandora’s wasteland roamed by dangerous creatures of various ferocity and stature, ranging from smaller spiderant spawn to the larger threshers. Whereas the Aztec priests preferred razor-sharp blades to remove human organs on an altar, the Bloodshot (priests?) make quick work of their victims, requiring little more effort on their part than hitting an electronic switch next to the altar and then picking up the loot Kincaid so generously rewards them for their devotion and button pressing.

In connection with this theme, much academic research supports the fact that real-world religious attendance and/or belief enhances both human and social survival, which may explain its presence among the Bloodshot of the Borderlands 2 universe.

In the medical health sphere, weekly religious attendance has been associated with improving and maintaining good mental health, increased social relationships, and marital stability (Strawbridge et al. 2001). Religious belief is correlated with better emotional health outcomes (Kowalczyk et al. 2020), the ability to cope with disease, recovery after hospitalization, and instills a positive attitude in those enduring difficult situations (Phelps et al. 2009; Puchalski et al. 2009; Albers et al. 2010).

Religion affords older people a better quality of life (Hall 1985), and older adults who participate in private religious activity before the onset of impairment appear to have a survival advantage over those who do not (Helm et al. 2000). Attending church significantly lowers the risk of dying, especially among women (la Cour, Avlund, and Schultz-Larsen 2006). Alternatively, a lack of religiousness was associated with poor breast cancer survival among African American women (Van Ness, Kasl, and Jones 2003). Many of these findings have led some scholars to highlight the importance of spirituality in clinical practice (Best et al. 2015).

But likely the greatest advantage religious belief and practice has for the Bloodshots of Pandora is its power to bind its community together during conflict, perhaps with a major goal being to acquire as many powerful munitions as possible to aid in battle for survival against the planet’s vicious beasts and opposing factions. Most of the bandits live in small settlements consisting of tents and makeshift structures with little defense against creatures like skags and sand worms and the elements, such as Pandora’s brutal flash freezes, which can all make for a quick and painful death for the bandit who finds himself or herself in the wrong place at the wrong time, which tends to happen quite a lot in the Borderlands’ universe.

In terms of social sustainability, research shows that real-world religion has positive effects on societies. It has significant potential for addressing social problems, and regular practice has beneficial effects in nearly every aspect of social concern (Fagan 1996). Religious involvement enhances an individual’s social capital in the form of family and peer networks (Muller and Ellison 2001; Pew Research Center 2016). Religious belief increases the chances of survival during times of global and national crisis (Kroesbergen-Kamps 2019; Sudarman and Reza 2023).

What provides valuable insight into the role of religion for the Bloodshots is that (real-world) religion not only serves to bind members together collectively but also aids their resistance and warfare efforts. Because of its power to encourage social formations, religions have emerged during times of conflict (Tammy 2017) and offer resources for resilience (Okihiro 1984; Laliberté 2017).

Religion therefore allows the Bloodshots to form social networks of coordination, solidarity, and, what the French sociologist Émile Durkheim (1858–1917), in The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (1912), called “collective effervescence.” These are charged moments when members of society merge to perform a religious ritual that serves to consolidate the unity of the group. Durkheim conveys collective effervescence as a feeling of electricity or energy to emerge from close contact between members of a group. This leads to states of collective emotional excitement that dominate society’s members. Bloodshot bandits coalescing in droves and hurling themselves into battle against the player, accompanied by their obviously unhinged war cries (e.g., “OH GOD IN HEAVEN, I CAN TASTE MY OWN MELTING FLESH!”), gives warfare a sacred quality that provides a sense of togetherness.

The Bloodshots experience a tentative existence threatened by many external (e.g., antagonizing human factions, roaming and terrortorial creatures, food shortages, and climatological phenomena) and possibly internal factors among themselves (on the assumption that their callousness and bloodlust may lead to cruelty among themselves too and not only towards outsiders). Together, these may serve to vitalize the internal religious impulse humans have, thus rendering the Bloodshots open to performing religious rituals (e.g., venerating Kincaid at a shrine in his honor through chanting prayer and blood sacrifice) and belief (e.g., Kincaid is a deity who will offer rewards for propitiating him).

References

Albers, Gwenda., Echteld, Michael., de Vet, Henrica C. W., Onwuteaka-Philipsen, Bregje., van der Linden, Mecheline H. M., and Deliens, Luc. 2010. “Content and spiritual items of quality of life instruments appropriate for use in palliative care: A review.” Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 40(2):290-300.

Al-Zaben, Faten., and VanderWeele Tyler J. 2020. “Religion and psychiatry: recent developments in research.” BJPsych Advances 26(5):262-272.

Best, Megan., Butow, Phyllis., and Olver, Ian. 2015. “Do patients want doctors to talk about spirituality? A systemic literature review.” Patient Education and Counselling 98(11):1320-1328.

Hall, C. Margaret. 1985. “Religion and Aging.” Journal of Religion and Health 24(1):70-78.

Heise, Tammy. 2017. “Religion and Native American Assimilation, Resistance, and Survival.” Oxford Research Encyclopedias. Available.

Helm, Hughes M., Hays, Judith C., Flint, Elizabeth P., Koenig, Harold G., and Blazer, Dan G. 2000. “Does Private Religious Activity Prolong Survival? A Six-Year Follow-up Study of 3,851 Older Adults.” The Journals of Gerontology: MEDICAL SCIENCES 55(7):401-405.

Kowalczyk, Oliwia., Roszkowski, Krzysztof., Montane, Xavier., Pawliszak, Wojciech., Tylkowski, Bartosz., and Bajek, Anna. 2020. “Religion and Faith Perception in a Pandemic of COVID-19.” Journal of Religion and Health 59(6):671-677.

Kroesbergen-Kamps, Johanneke. 2019. “Horizontal and Vertical Dimensions in Zambian Sermons about the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Religion in Africa 49(1):73-99.

la Cour, Peter., Avlund, Kirsten., and Schultz-Larsen, Kirsten. 2006. “Religion and survival in a secular region. A twenty year follow-up of 734 Danish adults born in 1914.” Elsevier Social Science & Medicine 62(1):157-164.

Laliberté, André. 2017. “Religion, Resistance, and Contentious Politics in China.” Review of Religion and Chinese Society.” Available.

Muller, Chandra., and Ellison, Christopher G. 2001. “Religious Involvement, Social Capital, and Adolescents’ Academic Progress: Evidence from the National Education Longitudinal Study of 1988.” Sociological Focus 34(2):155-183.

Okihiro, Gary Y. 1984. “Religion and Resistance in America’s Concentration Camps.” Phylon 45(3):220-233.

Pew Research Center. 2016. “7. How religion may affect educational attainment: scholarly theories and historical background.” Available.

Phelps, Andrea., Maciejewski, Paul., Nilsson, Matthew., Balboni, Tracy., Wright, Alexi., Paulk, M. Elizabeth., Trice, Elizabeth., Schrag, Deborah., Peteet, John., Block, Susan., and Prigerson, Holly. 2009. “Religious coping and use of intensive life-prolonging care near death in patients with advanced cancer.” JAMA 301(11):1140-1147.

Puchalski, Christina., Ferrell, Betty., Virani, Rose., Otis-Green, Shirley., Baird, Pamela., Bull, Janet., Chochinov, Harvey., Handzo, George., Nelson-Becker, Holly., Prince-Paul, Maryjo., Pugliese, Karen., and Sulmasy, Daniel. 2009. “Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: The report of the consensus conference.” Journal of Palliative Medicine 12(10):885-904.

Strawbridge, W. J., Shema, S. J., Cohen, R. D., and Kaplan, G. A. 2001. “Religious attendance increases survival by improving and maintaining good health behaviors, mental health, and social relationships.” Annals of Behavioral Medicine 23(1):68-74.

Van Ness, P. H., Kasl, S. V., and Jones, B. A. 2003. “Religion, Race, and Breast Cancer Survival.” The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 33(4):357-375.

[…] to be a practice run for my research. I did not select Borderlands itself for my doctoral study.See Analyzing Religion Through Video Games: Bandit Religion and Kincaid’s Shrine (Borderlands 2) (Part […]

[…] Analyzing Religion Through Video Games: Bandit Religion and Kincaid’s Shrine (Borderlands 2) (Part 2)See Part 4 (forthcoming) […]